- Published on

Reconciling Sin and Avidya, Part 1

- Authors

- Name

- Maa's Beloved

At the 1893 Parliament of World Religions, Swami Vivekananda famously proclaimed,

"Yes, the Hindu refuses to call you sinners. Ye are the children of God, the sharers of immortal bliss, holy and perfect beings. Ye divinities on earth — sinners? It is a sin to call a man so; it is a standing libel on human nature."

This statement reflects a prominent perspective held by Hindus more broadly on the Christian doctrine of sin. I recall a Hindu friend of mine once proudly stating, "the Christian sees man as sinful, dirty, condemned. Hinduism has a more charitable view; it understands that man is instead going from ignorance to Truth." In these perspectives, the Hindu doctrine of avidya or ignorance is seen as fundamentally different from and irreconcilable with the Christian doctrine of sin. At best, the doctrine of sin is seen as capturing only the surface of human error, whereas the doctrine of avidya instead uncovers its root causes.

This disagreement is not one-sided. Many Christians I know have also often expressed the sentiment that Hinduism, in reducing man's sin to mere ignorance, avoids any possibility of moral responsibility. If all evil is simply the result of ignorance, then sin loses its weight. We don't feel the heaviness of guilt or shame for our sin, nor the need for redemption. For Christians, the doctrine of sin highlights the gravity of human error. It is only by recognizing the depth of our sin that we can fully appreciate the magnitude of God's grace and the significance and necessity of Christ's sacrifice on the cross. The doctrine of sin is seen as highlighting a critical aspect of the human condition which the doctrine of avidya at best only understands in part.

I believe that these sentiments, in either direction, are grounded in misunderstandings of the other. I hope to show in the following writing that the doctrine of sin and the doctrine of avidya are not only fully reconcilable but also deeply illuminate one another. In particular, I hope to show that the force of sin in this world is none other than the force of avidya. If this can be established, the result will be that the Hindu will be much more willing to engage with the wealth of Christian study on the concept of sin and to consider the truth and merit in recognizing oneself as a sinner. Likewise, the Christian will also be less averse to the doctrine of avidya and more open to learning from the Hindu tradition's deep philosophical study on the nature of avidya, its root causes, and its cures. I believe that in understanding each other's conceptions of the reality of human error better, both traditions will find they come to a deeper understanding of their own.

The Doctrine of Sin

There are many hints that the concept of sin is more closely related with avidya than first meets the eye. Consider, for example, the word's linguistic roots. The Greek word for "sin," hamartia, is also more directly translated as "to miss the mark." This immediately suggests a potential similarity with avidya, which is explicitly defined by man's missing the mark of Truth. But is sin describing the same kind of "missing the mark"?

In the case of avidya, man misses the mark due to a distorted understanding of the self, existence, and God. But what about in the case of sin? A metaphor that shows up frequently in the Bible and Christian theology is the likeness of sin to a kind of sickness.

"On hearing this, Jesus said to them, 'It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.'" (Mark 2:17)

As Peter Bouteneff explains, "we know what health looks like, and sickness is a distortion of it." In the same way, in the doctrine of sin, Christ is the mark and represents what it is to be fully human, and our sin is then a distortion of that essence. But now recall that Christ is the logos, the universal divine reason, the eternal truth underlying all of creation. "He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together" (Colossians 1:17). Thus, sin is a distortion of the Truth, which is embodied in and is the essence of Jesus Christ.

But we're still missing something. Though both sin and avidya may be distortions of Truth, they may still differ in the cause of the distortion. Is the cause of the distortion of Truth in sin a lack of some kind of knowledge, as in avidya, or is it something more sinister like a direct choosing of falsehood in the full knowledge of Truth? In the following section, I hope to show that the latter is impossible.

The Impossibility of Sin in the Beatific Vision

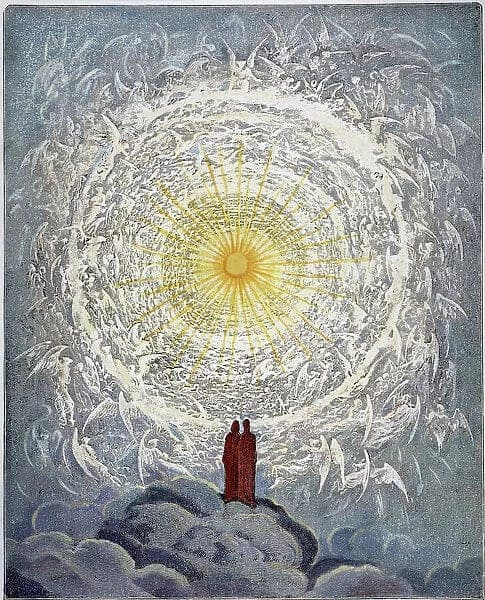

Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest Heaven - Gustave Doré (1868)

No eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him. (1 Corinthians 2:9)

For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. (1 Corinthians 13:9-12)

Throughout the Bible, there are prophecies of a "beatific vision" in which we will, by God's own grace, come to see God fully as He truly is, as fully as God knows us. This vision is then the full awareness of Truth, and so our previous consideration can be reframed as asking whether sin, or a willing distortion of Truth, is possible within the beatific vision. But if we willingly distort Truth in full awareness of it, it must be because there is something we seek, that we long for, which is not found in Truth. The Truth must somehow not satisfy us, allowing us to then consider that what will satisfy us may be found elsewhere.

But what do we long for? We can think of many examples. We long for happiness, fulfillment, love, joy, bliss, beauty, freedom, understanding, knowledge, and purpose. According to Plato, these longings can be unified in a single longing for the Good:

"Every soul pursues the good and does its utmost for its sake. It divines that the good is something but it is perplexed and cannot adequately grasp what it is or acquire the sort of stable beliefs about it that it has about other things." (The Republic VI, 505e)

But God is the highest Good; in fact, all good things are good only by virtue of the goodness that is God. This Truth is well recognized in both the Hindu tradition, which refers to God as sarva-maṅgala maṅgalyam, He who is the goodness in all things good, and the Christian tradition, where it is said, "every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows." (James 1:17). So every good we could seek in the world is in fact found in God. The greatest happiness, the greatest fulfillment, the greatest love, joy, bliss, beauty, freedom, the greatest understanding and knowledge, the greatest good are found in God, in Truth.

But in the beatific vision, when we see God in all His fullness, then we see too that the happiness we once sought elsewhere, the freedom we tried to preserve by rebelling against God, the understanding we searched for in all the various philosophies, the goodness which we longed for were in fact all always in Him. Seeing this completely, how can we nonetheless seek for something outside God? How can we still seek to distort Truth? It is impossible.

This stance is affirmed by the various prominent Christian theological traditions. In the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC), one of the primary documents defining Catholic theology, it is said of the beatific vision that

"For man, this consummation will be the final realization of the unity of the human race ... Those who are united with Christ will form the community of the redeemed, 'the holy city' of God, 'the Bride, the wife of the Lamb.' She will not be wounded any longer by sin, stains, self-love, that destroy or wound the earthly community. The beatific vision, in which God opens himself in an inexhaustible way to the elect, will be the ever-flowing well-spring of happiness, peace, and mutual communion." (CCC 1045)

Now, not all Christian traditions outside of Catholicism accept their understanding of the "beatific vision". For example, in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, though they believe in an ultimate vision of God, they do not accept the "Latin" notion of the beatific vision as a direct intellectual apprehension of God's essence. Instead, they emphasize theosis, union with God through participation in his divine energies, albeit while God's underlying essence remains unknowable.

Even in this view, however, it is maintained that sin is not possible after complete theosis. St Maximus the Confessor, who was highly influential in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, affirms precisely this:

"Whoever has shared in this divinization through experience and knowledge is incapable of reverting from what he, once and for all, truly and precisely became cognizant of in actual deed, to something else besides this, which merely pretends to be the same thing—no more than the eye, once it has seen the sun, could ever mistake it for the moon or any of the other stars in the heavens." (On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Response to Thalassios, Question 6)

"In them, their free choice clearly becomes sinless in conformity with their state of virtue and knowledge, since they are unable to negate what they have become cognizant of through actual experience." (On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Response to Thalassios, Question 6)

In fact, St Maximus' understanding of why precisely sin occurs very strongly aligns with an understanding of sin rooted in ignorance, i.e., grounded in an "erroneous judgement":

"Evil neither was, nor is, nor ever will be an existing entity having its own proper nature, for the simple reason that it has absolutely no substance, nature, subsistence, power, or activity of any kind whatsoever in beings. It is neither a quality, nor a quantity, nor a relation, nor place, nor position, nor activity, nor motion, nor state, nor passivity that can be observed naturally in beings ... evil is nothing other than a deficiency of the activity of innate natural powers with respect to their proper goal. Or, again, evil is the irrational movement of natural powers toward something other than their proper goal, based on an erroneous judgment." (On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Response to Thalassios, Introduction)

There are a few other hints in the Bible that the distortion of Truth in sin is caused by a lack of knowledge. We can perhaps find no stronger hint than what Jesus Christ himself said from upon the cross on which he was crucified: "Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do" (Luke 23:34). We find elaboration on this in the following verse in 1 Corinthians:

"But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, a wisdom which is hidden, which God ordained before the world, unto our glory: Which none of the princes of this world knew; for if they had known it, they would never have crucified the Lord of glory." (1 Corinthians 2:7-8)

If we knew the wisdom of God, if we understood the Christ, if we saw that he was Goodness incarnate, that in him was found all that we longed for, then we never would have crucified Him. Again, we find sin to be fundamentally incompatible with the complete perception of Truth.

Before continuing, I will consider a few objections to the above argument.

Objection from Free Will:

Objection: If it is impossible to sin after the beatific vision, isn't this a violation of free will? Is God not then forcing man to love Him?

Response: Consider a mother who loves her child deeply. Is it possible for her to, in the absence of any other competing pressure, will the destruction of her child? No, this is impossible. The nature of a mother's love, in its freedom, chooses each time to care for her child and wish for its well-being. Similarly, in the beatific vision, when the soul finally understands that all the Good it thus far sought in sin is in fact found in God, in its own freedom necessarily comes to love God.

In fact, if we consider this problem more deeply, we find that ironically the opposite of what we expect is true. We think we are free when we are able to sin, and hypothesize that our freedom is lost when we are no longer able to sin after the beatific vision. But through the above example, we find rather that true freedom is to be able to recognize the Good that we seek and to seek it. It is instead now that we are not free, where our passions, our ignorance, the satanic/asuric forces of the world lead us away from that Good which we long for. The very fact that we sin, that we choose that which misses the mark of what is in fact the deepest longing of our soul, is the evidence of our current bondage and need for true freedom.

In Romans 7:14-25, Paul describes the (highly relatable) experience of the sinner:

"I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. ... I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. ... So I find it to be a law that when I want to do what is good, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind, making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members." (Romans 7:14-25)

What could be a greater bondage than this? To long for the highest Good, and yet to be captured and led astray by the law of sin. Once again, true freedom of the will would be for the Truth to triumph in every cell of our body, and for us to be able live in the light of that Good which we fundamentally long for.

Objection from Original Sin:

Objection: Adam and Eve also saw God, but they nonetheless sinned, contradicting our claim.

Response: Admittedly, I imagine this objection is more likely to arise from Hindus or others outside the Christian tradition who (like myself) only have a limited understanding of the Biblical story of Genesis. The misunderstanding here is that while Adam and Eve may have had visions of God, they did not have the complete beatific vision to which we are destined. St Thomas Aquinas in fact argues for this being the case particularly on the grounds of the impossibility of sin in the beatific vision:

"The first man did not see God through His Essence ... unless, perhaps, it be said that he saw God in a vision ... The reason is because, since in the Divine Essence is beatitude itself, the intellect of a man who sees the Divine Essence has the same relation to God as a man has to beatitude. Now it is clear that man cannot willingly be turned away from beatitude, since naturally and necessarily he desires it, and shuns unhappiness. Wherefore no one who sees the Essence of God can willingly turn away from God, which means to sin. Hence all who see God through His Essence are so firmly established in the love of God, that for eternity they can never sin. Therefore, as Adam did sin, it is clear that he did not see God through His Essence." (Summa Theologiae, First Part, Q94)

So, with this, we conclude that sin is not possible in full awareness of the truth. Thus, where there is no ignorance, there can be no sin, and where there is sin, ignorance must be nearby.

Saint Aquinas' Objection: The Three Interior Causes of Sin

At this point, it's easy to think we have established that sin is fundamentally rooted in avidya. But, unfortunately, theology is not so simple. While we have shown that the existence of sin implies the existence of avidya, this does not necessarily imply a causal relationship between the two. For example, it may be that avidya is necessary to create the possibility for sin, but that some other force or initiator is needed to actually cause sin given this possibility.

This is in fact exactly what St Aquinas argues in his Summa Theologiae. For Aquinas, there are three interior causes for sin: ignorance, passions, and malice. Aquinas describes each of these causes as being manifestations of defects or disorder in certain aspects or "powers" of the soul:

Therefore even as sin occurs in human acts, sometimes through a defect of the intellect, as when anyone sins through ignorance, and sometimes through a defect in the sensitive appetite, as when anyone sins through passion, so too does it occur through a defect consisting in a disorder of the will, [as when anyone sins through malice].

The intellect is that faculty in us which, when properly ordered, manifests as knowledge or prudence, but when disordered and "missing the mark" of the Good, manifests as ignorance. Sins through ignorance then occur when one truly believes what is not their highest good to be so, as in the case of someone who believes that if they just got rich, they would be truly happy. The sensitive appetite, on the other hand, is the source of all our bodily impulses, including desires, lust, anger, delight, fear, anxiety, craving, etc. Sins through passion occur when one's sense of right and wrong is overwhelmed by a bodily impulse, as when someone attacks another in a fit of rage or commits adultery when overcome by lust. Finally, the will is in order when it is one-pointed in its pursuit of the highest Good as grasped by the intellect, but in disorder when it deliberatively wills what it knows to be evil. Sins through malice typically occur when one seeks some temporal good but, due to a disordered will, are tempted to attain it by means they know are wrong, unaligned with their highest Good, and not truly justified by their ends. For example, one may seek wealth through fraud, power or love through deception, pleasure through exploitation, etc., justifying themselves to themselves by saying they'll do it only once and that they will "be good" afterwards once they attain this temporal good they seek.

It's important to note that despite positing these three distinct causes of sin, Aquinas still accepts our earlier thesis that ignorance is necessary to create the possibility of sin. For example, in another passage, he identifies the particular kinds of ignorance which generate the potential for each of these kinds of sin:

Ignorance sometimes excludes the simple knowledge that a particular action is evil, and then man is said to sin through ignorance: sometimes it excludes the knowledge that a particular action is evil at this particular moment, as when he sins through passion: and sometimes it excludes the knowledge that a particular evil is not to be suffered for the sake of possessing a particular good, but not the simple knowledge that it is an evil: it is thus that a man is ignorant, when he sins through certain malice.

Still, except in the case of sins through ignorance, ignorance is seen only as the indirect cause of sin, creating only the possibility for sin, while these degenerated forces of passions in the disordered sensitive appetite or malice in the disordered will are understood as the direct causes which exploit the vulnerability of ignorance to cause sin. In this light, avidya is a necessary but not sufficient cause of sin, and so fails to account for the full reality of sin.

While the account Aquinas provides may successfully capture the relationship between ignorance, particularly as he defines it, and sin (I have a couple gripes with Aquinas' account of human psychology, but these are beyond the scope of this essay), I believe this account cannot be generalized to apply to avidya. This is because while avidya is traditionally translated as ignorance, I argue that Indian philosophy would see the classical western understanding of ignorance, including that of Aquinas, as capturing only a narrow kind of ignorance, that of intellectual ignorance. In order to flesh this out more completely, we must now turn to avidya and develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of its broader meaning.

The Doctrine of Avidya

From the untrue to the true, from darkness to light, from death to immortality - Priti Ghosh (2006)

We now turn our attention to the Hindu doctrine of avidya. The concept of avidya pervades the entire canon of Hindu philosophy including the Upanishads, the Gita, the Vedanta Sutras, the Tantric Agamas, the Puranas, and so on. One of the most clear and precise definitions of avidya can be found in the Patanjali Yoga Sutras.

anityā-aśuci-duḥkha-anātmasu nitya-śuci-sukha-ātmakhyātir-avidyā

"Ignorance (avidyā) is to misconceive the non-eternal (anityā) as the eternal (nitya), the impure (aśuci) as the pure (śuci), the sorrowful (duḥkha) as pleasureful (sukha), and the non-Ātman (anātma) as the Ātman (ātma)." (Patanjali Yoga Sutras 2.5)

We can see this kind of ignorance at play in much of what we consider sin in the world. Lust, greed, gluttony, and envy all arise from mistaking the transient for the lasting, from seeking the enduring bliss which in truth we can only find in God in the things of this world. Likewise, excessive pride or egotism stem from misconceiving this limited ego self as the source of its own greatness and strength, instead of understanding that all power, wisdom, and virtue are but reflections of divine grace flowing from God, the Supreme Self of all selves.

The Patanjali Yoga Sutras also highlight other afflictions that humans are exposed to which cause our suffering and unfulfillment, and then grounds each of these afflictions as rooted in avidya.

avidyā-asmitā-rāga-dveṣa-abhiniveśaḥ kleśāḥ

The afflictions (kleśāḥ)—the causes of man's sufferings—are ignorance (avidyā), egoism (asmitā), attachment (rāga), aversion (dveṣa), and a strong clinging to life / fear of death (abhiniveśaḥ).

avidyā kṣetram-uttareṣām prasupta-tanu-vicchinn-odārāṇām

Of these afflictions, ignorance (avidyā) is the breeding place (kṣetram) of all the others (uttareṣām), whether they are dormant (prasupta), attenuated (tanu), interrupted (vicchinna), or fully active (udārāṇām).

Here we find the central claim of the Hindu tradition, that all afflictions, all sin or missing of the mark of Truth arise fundamentally in one way or another out of avidya. The Gita gives us a further series of rich analogies to the state of avidya. Sri Krishna says,

dhūmenāvriyate vahnir yathādarśho malena cha yatholbenāvṛito garbhas tathā tenedam āvṛitam

Just as fire (vahniḥ) is covered (āvriyate) by smoke (dhūmenā), as a mirror (ādarśhaḥ) is covered by dust (malena), as an embryo (garbhaḥ) is covered by the womb (ulbena), so this [knowledge of the Truth] is covered by [worldly desires and anger]." (The Bhagavad Gita, 3.38)

Recognizing here that worldly desires and anger themselves are afflictions rooted in avidya, we see this picture of avidya as veiling or distorting the vidya which is in some sense already latent within us. This is very reminiscent of the biblical conception of the human as "made in the image of God." As Bouteneff explains,

"... what we have is one innermost self that is broken by sin. That sin, these foibles and passions, are not a second self; they are the dirt on the mirror. The Orthodox funeral service reminds us of our real identity when we sin, 'I am the image of your ineffable glory, though I bear the brands of transgressions.' We are, in our true selves, mirrors of the divine. But the glass is dirty, even bent." (How to be a Sinner, Bouteneff; emphasis added)

Bouteneff cites the 19th-century presbyter St John of Kronstadt who shares a similar sentiment:

"Never confuse the person, formed in the image of God, with the evil that is in him, because evil is but a chance misfortune, illness, a devilish reverie. But the very essence of the person is the image of God, and this remains in him despite every disfigurement." (My Life in Christ, St John of Kronstadt)

The Hindu similarly sees avidya as not the essence of man but a condition. The essence of man is pure untainted consciousness, Ātman. This Ātman cannot be cut, cannot be burned, cannot be wetted (Gita 2.23). It is eternal, all-pervading, stable, immovable, and primordial (Gita 2.24). It cannot be perceived by the five senses, nor conceived of by the intellect, and it is unchanging (Gita 2.25). Its inward essence is eternal bliss (Gita 6.21), and its outward expression is pure compassion and love for all beings (Gita 6.31, 12.13). In these and more ways, the Hindu also sees each human as in their essence sharing in the essence of God1.

And yet, as the Gita says, this mirror of pure consciousness is as if covered by the dust of avidya. As a result, though our inward essence is eternal bliss, we nonetheless suffer, and though our outward essence is pure compassion and love for all beings, we hurt even those who are dearest to us. In the following sections, we will explore avidya from various vantage points in which it seems to appear fundamentally different from sin, and establish whether these differences are grounded or misconceived.

Avidya is more than Intellectual Ignorance

When we first try to conceive of avidya as the root cause of all human afflictions and sin, we very quickly arrive at experiences which seem to outright contradict this possibility. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle makes the same observation when considering Socrates, who, taking a stance which seems at first quite similar to that of the Hindu, argued that lack of self-restraint does not exist: "nobody acts contrary to what is best while supposing that he is so acting; he acts instead through ignorance." Aristotle immediately points out that this perspective is "in contention with the phenomena that come plainly to sight ... For it is manifest that before he is in the grips of passion, a person who lacks self-restraint does not think, at least, [that he ought to act as he then proceeds to act]."

So often we find ourselves doing things we seem to know are wrong. The addict might realize that relapsing will not grant them lasting happiness, and yet choose to relapse, giving in to strong temptations while knowing that this does not lead to the good they seek. During an argument with their partner, someone might know that lashing out will not improve communication and foster love, and yet while knowing that this won't lead to the good they seek, they may fight, letting go in the momentary rush that comes with getting angry and lashing out. Hindu literature itself in fact gives accounts of this kind of conflict between knowledge and action. In the Mahabharata, Duryodhana expresses precisely such a struggle when asked why he sins:

jānāmi dharmaṃ na ca me pravṛtti

jānāmy-adharmam na ca me nivṛttiḥ

kenāpi devena hṛdi sthitena yathā niyukto'smi tathā karomiI know (jānāmi) what is Dharma, yet I do not pursue (pravṛtti) it.

I know (jānāmi) what is Adharma, yet I do not refrain (nivṛttiḥ) from it.

[It is as if] there is some deva or powerful force (devena) within my heart (hṛdi sthitena) that impels me, so that as it commands (yathā niyukto'smi), so I do (tathā karomi).

We are also reminded again of St Paul's expression in Romans 7:14-25, "I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. ... I can will what is right, but I cannot do it." Like Duryodhana, St Paul also describes feeling as if there were some force or "law of sin" within him which drove him towards sin:

"As it is, it is no longer I myself who do it, but it is sin living in me. ... For in my inner being I delight in God’s law; but I see another law at work in me, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin at work within me." (Romans 7:17-24)

Escaping the Problem

One way to resolve the seeming contradiction caused by these kinds of experiences is to simply deny their existence. This view suggests that while we may think we really do know that what we are tempted by is wrong even as we give in to that temptation, in truth, we give in only because we still at our core believe that it is right and worth pursuing, though we may repress this belief. Even if we did at some point earlier know in the true sense that the behavior was wrong, in the moment before we give in to temptation this knowledge must in this view somehow be altered, forgotten, or blurred, and this resulting ignorance is why we succumb to temptation. Aristotle in fact adopts precisely this position, preserving Socrates' original position while also accounting for lack of self-restraint as a susceptibility to one's knowledge being altered in the presence of desires or intense pleasures. In cases that particularly feel like the contradictory experience above, this view then explains them away as instances where the alteration to our knowledge is subtle enough or repressed thoroughly enough that we do not notice it and thus believe the knowledge is still there.

This explanation can certainly be found true in many situations. So often, we think and tell ourselves we don't want worldly pleasures, that we realize they won't ultimately fulfill us, only to find in a moment of self-reflection that we really do still believe and have hope that we will find our fulfillment in them (see Swami Medhananda's Self-Deception in Spiritual Life). We tell ourselves we believe one thing, but we really believe the other. But what about when we look within and find no such hidden belief? At the moment before giving in to temptation, we look in and see only that giving into this temptation is not what we really want, that it won't give us what we are longing for, and yet with this understanding, we witness ourselves overcome by desire and fall into sin. In our current explanation, what answer can we give to one who experiences this? We can only say that they didn't reflect deeply enough, that they are still lying to themselves and did in fact think the sin is good.

I find this explanation unsatisfying. While it firmly holds to the existence of a part of us which is still under the effects of avidya or ignorance, it is too quick to do away as an illusion or a lie the part of us that seems to know. I believe this view does, however, point to a core insight which necessarily follows from our earlier arguments regarding knowledge and sin, but which is understood more fully and clearly with a better understanding of the differences between intellectual knowledge, intellectual ignorance, absolute knowledge, and avidya.

A Fuller Resolution

Let's consider again something we had established earlier. In the section on sin, we showed that sin, or a missing of the mark of Truth, cannot occur in the presence of complete knowledge. Now, if we take this complete knowledge to be simply a full intellectual knowing, and thus take its absence or incompleteness to result from an absence of intellectual knowledge, i.e., intellectual ignorance, we actually recover our view from above. Here, you either know (intellectually) that something is not the Good and will not fulfill you, in which case it is impossible for you to give into its temptation, or you do not have this knowledge, and thus may pursue what you conceive of as possibly good. This binary kind of knowledge at only one layer of being leaves no possibility of there being a part of you that knows. If one believes they (intellectually) know while giving into temptation, we must conclude that their belief is a delusion, an instance of self-deception.

But the reason the above account falls short is because complete knowledge is not simply a kind of intellectual knowing, but is a knowing that pervades every level of our being, from the inner-most depths of our soul, to our intellect and mind, all the way to our very body. It is only in this complete embodied knowing which flows through every part of us, where we know God as God knows us, in which sin was shown to be impossible. Sin may still be possible, on the other hand, if we simply have intellectual knowledge without this complete knowledge.

But if complete knowledge is present at every level of being, beyond just the intellect, then ignorance, i.e., the lack or absence of knowledge can also be present at every level of being. Even if we have intellectual knowledge, it is possible that in the depths of our soul, in a way that is fundamentally different from any intellectual conviction, we still are drawn towards and seek the good in that which we intellectually feel to be wrong. This may be the truth to the kinds of expressions where one feels, "I rationally know this isn't for the best, but my heart still wants to try it." But we don't even need to look so deep into the depths of our soul to find instances of knowledge and ignorance beyond the intellect. Even the body itself, in sickness, can be found to not have knowledge or Truth manifest. The fact that misdirected desires or temptations arise at all in the body is manifest proof that the Truth of what is good is not present or "understood". This kind of sickness of the body can be seen most clearly in cases of addiction, where repeated exposure to extreme pleasures can condition the body to do everything it can, sending urges, hormones, etc., to induce this pleasure again. This too, in this picture, is a kind of ignorance of the body. It is this broader ignorance, which exists at all levels and not just the intellect, which Indian philosophy calls avidya2.

It is in fact particularly because of this holistic understanding of avidya that Indian spiritual practice is so diverse and goes beyond just reason and intellectual philosophizing. It includes both mystical and meditative practices aiming at direct experience of the Divine which will grant understanding and knowledge to the deepest depths of our soul, as well as embodied practices like hatha yoga, fasting, practicing moderation, breathing exercises, and more, which aim at healing avidya in the body and aligning it too with Truth3. With this deeper understanding of avidya, we can actually now preserve the core insight of our earlier explanation! When we give into the temptation of sin, it is correct to say that there must be some part of us that does not know that sin will not fulfill us, that still looks to it for its good. But this avidya is not necessarily found only at the level of the intellect. It can sometimes be found in deeper recesses of the soul or unconscious, or sometimes located even in trauma or sickness experienced by the body. We now find that as both the doctrine of sin and avidya suggest, even if we intellectually know something is wrong, we must still keep our guard up, because this is not the only angle from which the forces of sin or avidya can attack. In certain cases of addiction, it may simply be that the body needs time to heal, and in certain deeply internalized traumas, it may be that it is not reason or philosophizing that is needed, which will only reach the intellect, but a kind of cathartic self-forgiving love, or communion (as my friend Sebastian calls it in his essay, All of Life is Communion).

The Resolution to Saint Aquinas' Objection

This understanding of avidya also resolves our concerns about Aquinas' analysis of the relationship between sin and ignorance. When he speaks of ignorance, we see that he is speaking solely of intellectual ignorance. Aquinas posited that while intellectual ignorance was always what created the possibility of sin, it was often either the passions or malice which would come into contact with this possibility and cause sin4. But in light of our analysis above, we see now that each of Aquinas' three interior causes of sin can be understood as avidya at different levels of being. The passions, which Aquinas described as a defect in the sensitive appetite, are none other than avidya at the level of the body or lower mind. Malice, on the other hand, which was defined as a defect in the will, is avidya in the willing faculty of the mind. And finally, intellectual ignorance is of course avidya at the level of the intellect. We can now reframe Aquinas' position as arguing that while avidya manifested in the intellect is particularly what creates the possibility for sin, avidya in all aspects of being has the capacity to propel one towards sin given such a possibility. In this view, while there may be many different kinds of avidya that can cause sin, we can rightly understand avidya in its comprehensive sense to be the root cause of sin.

Our analysis also, however, gives us a way to potentially go beyond Aquinas by allowing for the possibility of sin that isn't grounded in avidya in the intellect. It allows us to account for the possibilities of the sorts of experiences we discussed above where we have clear intellectual conviction that something is wrong, and yet succumb to temptation and sin. Though we've shown that sin is not possible in the presence of absolute knowledge, and thus must be grounded in some form of avidya, it may still be possible in the presence of intellectual knowledge. This understanding of sin is better captured by the Orthodox Christian tradition which permits the possibility of involuntary sin, and describes the experience of sin in which one feels "a violence done to [them]," as if they are "tripped up without knowing how" (St Chrysostom, Homily 13 on Romans). We see this understanding of the fuller scope of sin in this prayer from the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom (emphasis added):

"... I pray to you, have mercy upon me, and forgive my transgressions, voluntary and involuntary, in word and deed, in knowledge or in ignorance. And make me worthy, without condemnation, to partake of Your pure Mysteries for the remission of sins and for eternal life. Amen."

With this, I believe we have made a strong case that avidya considered comprehensively is the root cause of sin, even under the most comprehensive understanding of the term. At this point, however, the careful reader may notice that our conception of sin at the beginning of the essay as a kind of sickness or defect differs a bit from the conception we find in Aquinas' objection, which sounds more like a bad deed or action. The key to understanding the subtle difference here is to understand the difference between the greek words hamartēma (ἁμάρτημα) and hamartia (ἁμαρτία), both of which are typically translated as 'sin'. Fr. Anthony Hughes explains the difference here as follows:

"The Greek word for sin in this case, amartema, refers to an individual act ... The word amartia, the more familiar term for sin which literally means "missing the mark", is used to refer to the condition common to all humanity."

So while hamartēma refers to sin in the sense of an individual sinful action or transgression (or 'pāpa' in sanskrit), as when one says "I have commited a sin," hamartia refers to the proclivity towards sin within us or 'concupiscence', to the "law of sin" that St Paul speaks of, the spiritual condition or sickness that is the root of sinfulness. When using the word sin, St Aquinas consistently refers to sin as an action, as hamartēma. Here he is following an emphasis that finds its roots in St Augustine who argued that sin in the proper sense was the individual sinful action, and that concupiscence (or more broadly the condition of hamartia) was only somewhat imprecisely called sin. St Augustine says,

"But although this [concupiscence] is called sin, it is certainly so called not because it is sin, but because it is made by sin, ... or because it is stirred by the delight of sinning"

He explains instead that "they are sins which are unlawfully done, spoken, thought, according to the lust of the flesh, or to ignorance," suggesting again the emphasis on sin as action or hamartēma. In contrast to this, the Orthodox tradition more commonly places emphasis on sin as hamartia, as a condition or disease that needs healing.

Regardless of which of these two concepts is most properly referred to as sin, we can now see in light of the above arguments that when we consider sin as hamartia, avidya is not a distinct cause of sin, but rather none other than sin. Avidya and hamartia alike are the spiritual condition or sickness which manifests in the intellect, the will, the sensitive appetite, and potentially other aspects of our being as defects or misalignments with the Truth their essences point towards. On the other hand, when we consider sin as hamartēma, then avidya and hamartia alike are the root causes of sin. It is this "law of sin" or hamartia or avidya within us which, when expressed in thought, word, or deed, becomes hamartēma.

So far, we have made philosophical arguments for the reconciliation of sin and avidya based on their most core definitions in either tradition. Still, even if the doctrines of sin and avidya are philosophically reconcilable or even found to be the same, it might be that the pragmatic ways people understand and engage with the terms differ in fundamentally irreconcilable ways. In the following sections, we will consider some common ways in which the Christian engagement with the doctrine of sin seems to differ with the Hindu engagement with the doctrine of avidya.

The Theology of Human Poverty vs the Theology of Human Potentiality

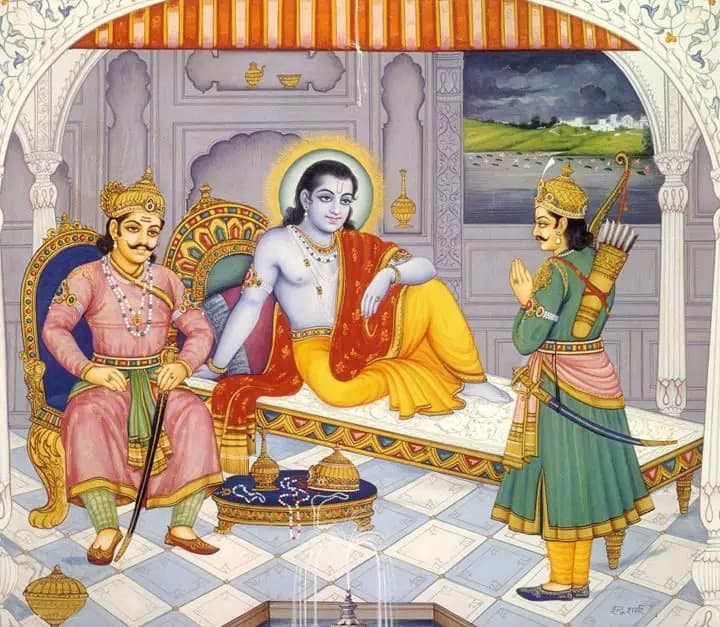

When offered the choice between Krishna's mighty army or Krishna himself as a guide, Duryodhana (left), trusting in worldly strength and human potentiality, chooses Krishna's army. Arjuna (right), having faith in the power of grace alone, chooses Krishna himself.

Earlier in the last section, we discussed a variety of "techniques" or spiritual practices which the Hindu approach to spirituality incorporates in order to resolve avidya at all levels of being beyond just the intellect. This language of "technique" leads quite immediately to another concern: the doctrine of avidya differs from the doctrine of sin in espousing a theology of human potentiality rather than one of human poverty. This idea was introduced by Sean McGrath on his podcast Secular Christ, in the episode titled Christ is not an Archetype, and further discussed by my friend Sebastian in his essay An Invitation to do Nothing. In the podcast episode, McGrath presents the difference as follows:

"... the philosophy of human potentiality doesn’t need grace. All you need is awakening. All you need is training, instruction. You just need to be liberated from your illusions. You have to withdraw your projections. It’s all in you. You are divine. You are the divine and insofar as in your ordinary consciousness, you think that you aren’t, your ordinary consciousness is illusory. It’s a trick that your mind is playing on you. So you can use techniques to correct that: yoga, meditation, for example. Or you can simply have an enlightenment experience. And then what you find yourself affirming is something that has been affirmed over and over again throughout the world’s religions all through the ages, particularly back into Hinduism. And that’s it: the Brahman is Atman; God is the soul and the soul is God. That’s the philosophy of human potentiality, and it is deeply opposed to Paul’s Christianity.

Because in Paul’s Christianity, we get the opposite thesis. We get the thesis that the human being is not potentially divine. The human being is actually fallen. If the philosophy of human potentiality says we have all that we need, we’re essentially divine and all that’s required is awakening, the philosophy of human poverty says the opposite. We do not and cannot of our own efforts reach divinity. What is needed is something like a divine intervention.

All is by the Grace of God

There are several related concerns here regarding differences between sin in Christianity and avidya in Vedantic Hinduism, so it will help to deal with these one-by-one. To begin, there is this central sense that Vedantic Hinduism seems to think "we have all that we need," that the highest can be attained purely through the power of our own human essence, or in other words, that there is no need for anything like the "grace" of God, or maybe even for God at all. McGrath contrasts this view with St Paul's Christianity, elaborating later in the podcast as follows:

For St Paul, we are just completely lost without the act of God saving us in Christ. There was—there was no hope for us without Christ. We were entirely doomed without him. And what we receive in Christ is pure gift. And so Paul is constantly chiding his disciples not to get puffed up with grace, with their possession of the doctrine of salvation. He’ll say to them, “What do you have that was not given to you? What makes you so important?” And Paul himself never speaks like a Hindu sage who has realized, through effort and technique, the insight. It’s rather, something befell him. He was on the road heading the opposite direction when Christ beseeched him. So this emphasis on intervention, direct divine intervention into a human situation that is totally going in the wrong direction."

I believe that Vedantic Hinduism is in fact much closer to this picture above than it seems. In order to make this comparison, it will be helpful to reference a few lines spoken by the Lord Sri Krishna to Arjuna in the Gita5:

"From me alone arise the varieties in the qualities amongst humans, such as intellect, knowledge, clarity of thought, forgiveness, truthfulness, control over the senses and mind, joy and sorrow, birth and death, fear and courage, non-violence, equanimity, contentment, austerity, charity, fame, and infamy." (Gita 10.5)

"Whatever glorious or beautiful or mighty being exists anywhere, know that it has sprung from but a spark of My splendour." (Gita 10.41)

We are nothing without God. Anything that we are, we are only by the virtue of God. This kind of thinking is firmly ingrained into the core of the Hindu psyche, and Hinduism cannot be understood without understanding this complete immanence of God. This complete immanence is accepted so strongly in fact, that even to say, "we are nothing without God" does not make sense. What "we" is there to speak of as "nothing" without God? We have no existence without God, let alone strength or virtue or achievement. Our existence and every aspect of our being are the fruits of God's grace.

Understanding this, it never makes sense for a Hindu sage to claim that they have gained insight or realization through the application of effort or technique arising out of their limited ego-self separate from God. It is by the grace of God that the sage had the longing for truth, it is by grace of God that the sage discovered or developed any technique or found the strength for any intense effort, and it is by the grace of God alone that this effort culminated in any inner peace or deeper understanding. As Sri Ramakrishna says, "Though you try a thousand times, nothing is achieved without God’s grace. Without His grace, you cannot see Him." To a sage who does feel themselves, in their ego-self, aggrandized by their achievement of knowledge or realization, one would be right to ask them as McGrath suggested, "what do you have that wasn't given to you?" Again, this view is firmly and clearly established in the Gita, and so is fundamental to Vedantic Hinduism, cutting across differing schools of thought which may take different stances on the precise relations between Ātman and Brahman.

Now, when it comes particularly to Vedantic schools which assert that Ātman is Brahman, McGrath may argue that the conception of grace no longer makes sense. The source of this grace is no longer God, but just the human self. Now, it's worth noting that to develop even a somewhat adequate account of what precisely is meant by such mahāvākyas (great statements) which assert the identity of Ātman and Brahman would require much, much more historical and philosophical contextualizing and work than would be reasonable to try to tag onto this essay. But something that is important to understand is that these mahāvākyas are always speaking first of God. It is not that we realize that God is none other than this human self (reducing God to our limitations), but that our true Self is none other than that God whom we worship and who's grace we enjoy the fruits of. Our conception of our "self" grows beyond the limited ego-self into a recognition of the infinitude which underlies it. It is never the limited ego or mind-body complex that is asserted to be God, but rather the ground of being or awareness by virtue of which or in which they exist. It is this ground of being which these Vedantic schools claim to be what we truly are, which is in the most true sense our "self". There's much more nuance to unpack here, but I'll leave it for another writeup.

Techniques or Practices are also Gifts of Grace

This conception of grace also allows us to vindicate the use or emphasis on "techniques" as unique to the theology of human potentiality. When all techniques (or yoga) are seen as granted themselves by the grace of God, then technique too is accepted as a gift, rather than as a seeking out of one's own strength. I believe this is understood by the Christian as well, for example, in recognizing and accepting the tremendously nourishing gift that is granted by God to man in the form of the Lord's Prayer and Jesus' teachings on how to pray. He says,

“And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners to be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. But when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you. And when you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words. Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him.

This, then, is how you should pray:

‘Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name,

your kingdom come,

your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us today our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors.

And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.’" - Matthew 6:5-13

When we accept this gift, and pray as Jesus taught, we are not trying to apply some technique ourselves so that we may of our own strength attain to some relationship with the divine. No, we are accepting the gifts of grace. God Himself has granted us ways for us to commune with Him!

In the podcast, McGrath makes a case for how the practice of contemplative Christianity differs from that of other contemplative traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism. He says,

"there’s one thing about the contemplative Christian path which is quite unique and that is that it is a path without technique. There’s no method required. There’s no special yoga needed. If yoga helps, do it. But, you know, if—maybe walking in the woods is the place where you hear the voice of God. Or maybe you’ve got to go out and serve your community until you’re exhausted and beaten to the ground. It doesn’t make any difference, because we’re not trying to alter our consciousness through method. We are rather trying to receive a gift that has already been given, and is always, always active—which is the grace of Christ redeeming the world on the Roman cross."

The key is precisely what is said at the end. What we are trying to do is to receive a gift that has already been given and is always, always active. Even in the Indian tradition, the aim of practice or "technique" is not to of our own strength attain to some realization, but to open our heart and make ourselves more receptive or ready to receive God's grace. Sri Ramakrishna says,

"The winds of God's grace are always blowing, it is for us to raise our sails."

In this light, we do whatever practice we do, so that we may raise our sails and open our arms to grace. We do meditation practices, so that our mind, which typically is so insistent on running around after its own thoughts, asserting its own ideas about how our world should be, can be quietened just for a bit to make space for the possibility of grace. We fix our hearts and minds on God in devotional singing. We engage in selfless service, seeking to serve God through the people in the world. We may contemplate the works of saints who have experienced the truth of God, or share in holy company with other lovers of God. We may also spend time taking in the beauty of God in nature on a walk in the forest. And sometimes, we may do nothing more than sit and listen. All these practices, each of which we are able to practice only by the grace of God, exist only to cultivate a deeper surrender within us which quiets the ego and its desires and makes space for God. And for these practices, I am grateful, because they have given me, someone who otherwise had no intuitive knowledge of how to worship or pray, opportunities for communion with that God whom I love.

Now, I would like to note that I definitely do not deny that much of neo-Vedanta and modern day Hindu spirituality takes the form of the theology of human potentiality, forgetting the role of grace. Aspirants will run around from meditation retreat to meditation retreat, looking for that one technique or practice which will get them to realize oneness with Brahman and experience an altered state of consciousness filled with bliss. What I hoped to establish in this discussion is that this kind of perspective is fundamentally missing a crucial piece of the full picture that makes up Vedantic Hinduism. In this fuller view, we see that the doctrine of avidya, like the doctrine of sin, sees human shortcomings or error as fundamentally resolved only through God's grace.

The Inherent Divinity of Man

One sentiment McGrath expresses that the Hindu will actually have trouble seeing reconciled in their own tradition is when he says that, "the human being is not potentially divine. The human being is actually fallen." The Hindu may be able to accept the latter; we cannot deny that man is under the influence of avidya and thus falls short of Truth. But the divinity of man by virtue of God is essential to the Hindu tradition.

I am skeptical, however, that even McGrath is himself committed to truly denying the divinity of man. All these quotes are of course taken from his podcast episode and it is easy to not be the most precise in that kind of format. Citing again the quote by St John of Kronstadt, I believe the Christian tradition is also in the same way committed to the divinity of man.

"Never confuse the person, formed in the image of God, with the evil that is in him, because evil is but a chance misfortune, illness, a devilish reverie. But the very essence of the person is the image of God, and this remains in him despite every disfigurement." (My Life in Christ, St John of Kronstadt)

McGrath also seems to point this out at a later point in the episode where he mentions that the theology of human potentiality and the theology of human poverty are unified in a non-dual relationship in mystical Christianity. He says,

"There is a solution to the dichotomy, which is a non-dual relation between them. That poverty and potentiality are not two. And in fact, that’s precisely what you get in effective mystical Christianity. We are without God: hopeless, doomed, and lost, as Luther says. You know, what we call true is in fact false. What we call good is in fact evil. ... but with this intervention ... the Christ event has altered human nature. And so the being that was once fallen and addicted to falsehood is now a redeemed being. Christ is now an immanent principle in human nature. So we’re both, but it’s nevertheless—the Christ is not a human potential. The Christ is a gift. Even if it’s now an inalienable part of who we are. And Paul’s clear that it’s not simply those who hear the gospel who have been changed. It’s everyone. Whether you grew up hearing the letters of Paul, or whether you grew up reciting mantras in a Tibetan monastery, you are altered. You are now part of the Christ. So in their origins, these two philosophies are opposed to each other, and in the experience of redemption, they are non-identical and non-different. They are non-dual one."

In this view, McGrath makes the point that Paul's Christianity is not "just a theology of poverty," but rather a "theology of redeemed poverty." Without God, we are nothing, but through the gift of grace, the gift of Christ, we are granted divine nature as an inalienable part of who we are. The view McGrath presents here, however, still seems to hold that this alteration of man and granting of divine nature occurred in time through the blood the Christ shed in his sacrifice on the cross about 2000 years ago. It seems here then that those who lived before the historical Christ event were truly without God as McGrath puts it. It's not clear to me that this is the broader understanding in the Christian tradition, particularly in light of the St John of Kronstadt quote from earlier. In any case, this kind of view is certainly one the Hindu would be unable to fully accept, especially since God's grace and forgiveness of man's sin had been revealed in another part of the world, centuries before the Christ event, through Sri Krishna's promise to Arjuna in the Gita.

A Hindu religious pluralist who fully accepted the Christ as a true incarnation of God would likely see Christ's sacrifice on the cross forgiving our sins as rather an eternal event which has always been happening (a view reminiscent of Meister Eckhart's understanding of unceasing incarnation: "The eternal birth which God the Father bore and bears unceasingly in eternity is now born in time ... St Augustine says this birth is always happening."). While the Christ's sacrifice was made most apparent to us in the historical sacrifice where the literal blood of the Innocent One, God incarnate, was shed, God has been in a deeper sense bleeding for the sins of humanity throughout all of time. When a mother's child undergoes deep suffering in the world, she herself feels wounded in a way that is deeper than any physical wound she could experience. In a similar way, God has always had to pay for the sins of humanity, and yet the love of God knows no bounds. Even in the depths of our sin and avidya, God has forgiven us and gifted us at every moment of history with grace and pure love, a love which can be experienced and accepted when the heart is open to it and the soul is ready to receive it with arms open. Sri Aurobindo makes this clear in his rendering of Sri Krishna's promise to Arjuna:

"Those who aspire in their human strength by effort of knowledge or effort of virtue or effort of laborious self-discipline, grow with much anxious difficulty towards the Eternal; but when the soul gives up its ego and its works to the Divine, God himself comes to us and takes up our burden. To the ignorant he brings the light of the divine knowledge, to the feeble the power of the divine will, to the sinner the liberation of the divine purity, to the suffering the infinite spiritual joy and Ananda. Their weakness and the stumblings of their human strength make no difference. “This is my word of promise,” cries the voice of the Godhead to Arjuna, “that he who loves me shall not perish.”"

The Shame of Sin

St Peter after he has denied the Christ, his eyes red with tears and hands clasped in prayer - Jusepe de Ribera (1612)

Before wrapping up, we will attempt to resolve one of the strongest tensions at the root of much of the typical Hindu rejection of and aversion towards the Christian doctrine of sin—its association with shame. This shame associated with Christian sin is often spoken of pejoratively in the common culture as "catholic guilt". In writing this essay, I have had many conversations with close practicing Hindu friends of mine and after trying to make all of the above cases for the doctrine of aviyda being more intimately related to the doctrine of sin than it seems, the conversation would in almost every case arrive to this tension regarding the shame that seems so closely tied with the doctrine of sin.

Before we consider whether this attitude towards sin constitutes a critical or irreconcilable difference between sin and avidya, it will be helpful to develop a more thorough understanding of the role shame plays in actual Christian practice. I'd also like to note that the following section is heavily influenced by Peter Bouteneff's book How to be a Sinner, and so I highly recommend the book to anyone interested in a deeper understanding of these topics.

A Healthier Picture of Shame in Christianity

"Take from me the heavy yoke of sin, and in your compassion, grant me tears of compunction." (The Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete)

"Give me understanding, O Lord, that I may weep bitterly over my deeds." (The Canon of Repentance)

A fascinating theme that reoccurs frequently in Christian prayer is that shame or remorse, far from being simply an unfortunate reality of human experience that we must endure, is instead something immensely cherished and valuable, so much so that the saints have prayed to be gifted it by God's grace. Why would anyone ever pray to be granted shame? The key is that shame often comes not alone, but together hand-in-hand with longing.

Consider what may happen if we have no shame, if in seeing our reality, we perceive no way in which we fall short of our nature or of what we could be. In this kind of setting, one might reasonably find no reason to long for God. If our condition here, as it is, is utterly without fault, if there is no avidya or sin, no sense in which we are sick or missing the highest Good which we intrinsically long for most, then it is best to simply enjoy this reality as it is. Only one who is delusional would seek for an other while knowing the highest Good was already in their possession (in fact, we demonstrated this earlier to be impossible).

But the truth is that we are afflicted by avidya, we are sick with sin, and so much worse than shame would be to be ignorant of this reality. Father Sophrony explains,

"To apprehend sin in oneself is a spiritual act, impossible without grace, without the drawing near to us of divine Light. True contemplation begins the moment we become aware of sin."

It is only when we become aware of sin that we contemplate whether there is a possible way to heal, and in turn develop a longing for Him, in whom all sin melts away, in whom lies our salvation and fulfillment. But shame is precisely the natural human emotional expression of this coming into awareness of sin. Sin is sin, by virtue of missing the mark of the Good, and the Good is good by virtue of being that which we intrinsically long for. Of course it hurts then when in becoming aware of our sin, we discover how consistently we have strayed from that true object of our love. And so we pray that God grants us an awareness of sin, that He grants us tears of compunction, so that in repentance, we may draw nearer to Him.

"Through love of pleasure has my form become deformed and the beauty of my inward being has been ruined.

The women searched her house for the lost coin until she found it. Now the beauty of my original image is lost, Savior, buried in passions. Come as she did, search to recover it." (The Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete)

Now, all this being said, we simply cannot deny that though shame can sometimes arise as a catalyst for a deeper longing of God, it can also very often take a more insidious, destructive form. In this form, shame does not lead us closer to God, but rather drives us deeper into despair, self-hatred, and even more sin. Bouteneff warns us very clearly of this possibility

"Feelings of repressed guilt and shame, unnamed, unchecked, untreated, can lead to emotional and physical illness. When turned inward, unchecked shame leads to depression, and possibly towards suicidal tendencies; when turned outward, it can lead to toxic anger, and possibly towards the abuse of oneself and others. In fact, people can seek to offset their own shame by shaming others. In one very common example of this, a man can so despise the fact that he is sexually attracted to other men that he channels that hatred towards others, especially other people with same-sex attraction. Shame can furthermore lead to or exacerbate compulsive and addictive behaviors, notably the abuse of substances, food, sex, or money. All of these are deeply serious concerns, a matter—sometimes literally—of life and death. Guilt and shame can act like a poison."

This dichotomy between a "therapeutic shame" which saves and a "neurotic shame" which poisons, as Bouteneff puts it, is in fact recognized in Christian scripture. In his second letter to the Corinthians, St Paul writes,

"For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation without regret, whereas worldly grief produces death. For see what earnestness this godly grief has produced in you, but also what eagerness to clear yourselves, what indignation, what fear, what longing, what zeal, what punishment!" (2 Corinthians 7:10)

And so it is this godly grief which the saints pray for, a shame which doesn't end in itself, but which in repentance draws the soul closer to God. Through this healing and cleansing process of repentance, the soul emerges "without regret," and instead rejuvenated with renewed courage, joy, and faith.

The Role of Shame in Hinduism

Having given a charitable account of the role of shame in Christianity, we can now consider whether there is reason to be averse to it from the standpoint of the doctrine of avidya and Hinduism. Far from there being such a reason, I believe in fact we can recover a kind of emotional expression in Hinduism quite similar to the "godly grief" spoken of in Christianity, the seeds of which lie in the Hindu concept of vairāgya. Vairāgya is often translated as "dispassion" or "detachment," so that in the context of Hindu spirituality6, vairāgya is dispassion for worldly pleasures and pursuits, and worldly life as a whole. While these translations of vairāgya emphasize the equal-handedness of it—the dispassion or detachment is from all sense experiences, pleasureful and painful alike—they lose in translation the intended intensity of vairāgya. An alternative translation of vairāgya is also "disgust" or even "loathing". The picture here is one who, realizing as St Augustine does that "wherever the soul turns, unless towards God, it cleaves to sorrow," utterly rejects worldly temptations in disgust, and turns in intense longing towards the Lord. One with vairāgya realizes that "you cannot serve both God and mammon," and disdains anything that may pull them away from God, and, as described in the Ashtavakra Gita, "shuns the objects of the senses like poison."

We can see this kind of intense vairāgya in this story of Sri Ramakrishna:

"Once, Mathur gave [Sri Ramakrishna] an expensive shawl. ‘He took it cheerfully,’ Swami Nikhilananda wrote, ‘and like a boy showed it to others.’ But soon, his mind went to the evil temptations that the shawl could lead him into. He threw the shawl on the ground, ‘and began to trample and spit on it. Not content with this, he was about to burn it when someone rescued it.’ The same sort of thing happened another day. He had gone to Hriday’s house. He came out to leave. He was wearing a scarlet silken cloth, had a gold amulet on his arm, and his mouth was crimson from chewing paan. People had gathered to see him. 'But they see me every day,' he said. 'Why have so many gathered?' he inquired. Hriday said that they had come to see him especially because he looked so handsome in that particular dress. That was enough to shock Sri Ramakrishna. ‘What, people crowding to see a man! I won’t go. Wherever I may go, people will crowd like this.’ He returned to his room and took off the robe in utter disgust."

Seeing the temptations towards grandiosity, fame, and admiration that wearing the elegant shawl created in him, Sri Ramakrishna could not bear anything that may pull his heart away from God. In a show of vairāgya, he trampled, spit, and almost burnt the shawl.

Now, in this story, it is convenient that the shawl was something so easily separable from him, that recognizing its power to pull him away from Whom he longed for most, Sri Ramakrishna could immediately throw the shawl away from him. But what about when we find that the worldly tendency which is pulling us away from God is within us, in the form of addictive tendencies or strong desires. If separating ourselves from material possessions which tempt us is difficult, separating ourselves from the core desires and habits within us which cling to worldly life can often feel nearly impossible.

So what does the soul do? It cries and prays, O God, it is you alone who can free me from the grips of avidya, these shackles which drive me again and again to forget You and seek bliss in worldly pleasures, even though I am certain all I seek is found in You.

Notice here, just as in the case of godly grief, this kind of vairāgya is a spiritual gift because it comes hand-in-hand with an intense, deep longing for God. We see further examples of this in the following stanzas from a poem in the Tiruvaymoli, a famous collection of poems written by Nammalvar, one of the twelve Vaishnava Alvars:

In days past, I didn't do good, nor did I not do bad I lived to savour trivial things. I strayed. Supreme one, creator of countless lives, when will I reach your bright golden feet?

Heart, you suffered without end, devoid of wisdom, drowning in a life doomed by deeds. How do I reach the flame of wisdom, the one who is everywhere, the one without end. How do I reach Kaṇṇaṉ?

I haven't abandoned acts that bring sorrow I haven't worshipped your feet without pause ancient pervasive beautiful Kaṇṇā my supreme light, I call out to see you. Where should I call to see you?

I cry out from the tangle of my wickedness stumbling through many paths, growing wretched. Many a time do I call my Sire, who once shepherded the cows, and spanned all the worlds. When and how will I draw near him?

We see here again that vairāgya is not a shame or disgust which ends with itself, which recognizing and rejecting that which falls short of the Good, turns inward in a neurotic self-hatred. Rather, like godly grief, vairāgya follows the rejection and disgust towards error within oneself immediately with a greater and deeper longing for God and truth.

The Degenerate Forms of Sin and Avidya

We have established that both the Hindu and Christian traditions see godly grief as a spiritual gift that moves one towards God. So why is the Hindu still so averse to even the slightest thought of Christian shame? I claim this is a response to the direction in which Christian shame tends to degenerate when not fully understood. As we discussed earlier, in its degenerate form, the godly grief of Christianity decays into a crippling self-hatred leading to drastic self-image issues and even suicidal ideation. The Hindu tradition is particularly wary of this possibility of degeneration, and so has always placed great emphasis on not dwelling on sin. Vairāgya, a disgust and strong rejection of sin, is good, so long as it turns the attention quickly away from sin and towards God in longing and prayer.

We can see this emphasis on not dwelling on sin and turning the mind instead to God in the following discussion of Sri Ramakrishna's teachings.

Sri Ramakrishna taught his devotees not to dwell on weakness and sin. He urged them to cultivate faith in the divine name and resolve to live a new life: "If a man repeats the name of God, his body, mind, and everything become pure. Why should one talk only about sin and hell, and such things? Say but once, 'O Lord, I have undoubtedly done wicked things, but I won't repeat them.' And have faith in His name." He taught that God's grace transforms even the worst sinner into a pure soul: "Heinous sins—the sins of many births—and accumulated ignorance all disappear in the twinkling of an eye, through the grace of God. When light enters a room that has been kept dark a thousand years, does it remove the thousand years' darkness little by little, or instantly? Of course, at the mere touch of light all the darkness disappears."

We see the same emphasis in this urgent teaching by Sri Ramakrishna:

"Give up all such notions as: ‘Shall we be cured of our delirium?’, ‘What will happen to us?’, ‘We are sinners!’ One must have this kind of faith: ‘What? Once I have uttered the name of Rama, can I be a sinner any more?’”

Given the potential for Christian shame to degenerate, it is greatly understandable for the Hindu tradition to give these warnings and urge one to instead turn to the Lord, remembering that even the greatest sickness or sin is erased in an instant in God. The teachings are furthermore correct. It is true that if we have faith in God and turn to Him in surrender and longing, we will be saved and freed from our sins—sarva‑pāpebhyo mokṣayiṣyāmi (Gita, 18.66). This is affirmed even by the Christian tradition in Romans 10:13, "For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved."

The problem, however, is that while the godly grief of Christianity has a degenerate form, the godly grief of Hinduism does too. Whereas Christian practice can tend towards an excessive dwelling on sin, Hindu practice in its degenerate form can decay into a blindness of sin. This blindness manifests most commonly as spiritual bypassing, using partial understandings of spiritual truths to justify oneself as one is and ignore any need for change.

I'm reminded of a famous story of Sri Ramakrishna encountering this kind of degenerate spiritual bypassing first-hand. Having learned of a monk who was rumored to be having an affair, Sri Ramakrishna confronted him. In his defense, the monk said, "Vedanta teaches that everything is Maya. Now if everything is a dream, how can my affair alone be real? It's also part of Maya." Sri Ramakrishna retorted, "I spit on your Vedanta!" Going into the details of the doctrine of maya and the ways it is misunderstood is beyond the scope of this essay, but this story illustrates the tendency for such partial understandings of spiritual truths to result in spiritual bypassing, and a blindness to one's own error and need for change.

Swami Medhananda also comments on the form this spiritual bypassing takes in today's culture of over-commercialization of spirituality to the masses, where it is preached, "You can have your cake and you can eat it too. Go ahead and do whatever you're doing already. No need to change anything in your life, but you have the added advantage of calling yourself spiritual." And so lust is mistaken for love, drug-induced experiences are mistaken for lasting spiritual transformation, and most generally, as Swami Medhananda puts it, bhoga (the path of gratification) is mistaken for yoga (the path of perfection and divine union). The Gita speaks of such practitioners as mithyā-ācāraḥ, hypocrites or 'those whose conduct is false,' who may restrain their organs of action under the pretense of meditation, but whose mind remains dwelling on the objects of the senses (Gita 3.6).

All this is to say a spiritual stagnance caused by a blindness to sin is just as bad as a stagnance caused by a neurotic obsession with sin. The healthy middle path offered by both the Christian tradition and the Hindu tradition is a godly grief which truly apprehends sin or avidya in oneself, and in this recognition, turns in greater longing towards God seeking healing and communion with the Highest Good. It is also worth noting that while I argue that Christianity and Hinduism tend to degenerate in opposite directions, this is not to say that they are immune to the opposite degenerations. Orthodox Brahmanical Hinduism with strict social norms for what is right and wrong (many of which are influenced by underlying casteism) can sometimes result in a kind of neurotic shame that leads to self-hatred and fear when someone has accidentally done something wrong. On the other hand, Christianity also sometimes develops more liberal strains which claim to focus on the Christ's message of all-encompassing love and peace (after all, the Christ loved even the tax collectors and prostitutes), singing 'kumbaya!' and affirming all lifestyles, forgetting that the Christ said, "Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword." (Matthew 10:34).

Different Responses to the Recognition of Sin

Now the above discussion can make it seem like what we are looking for is an ideal intensity of shame. That is, both no shame and too much shame lead to spiritual stagnance, so we need to find the goldilocks 'just right' amount of shame that leads to longing. But this is the wrong way to think about it. Again, as in 2 Corinthians 7:10, what makes godly grief godly isn't the intensity of the grief or even the particular kind of emotional response experienced or expressed, but the fact that it 'produces a repentance which leads to salvation without regret.' More generally, the criterion for a good emotional response to sin is one which apprehends the sin (and does not turn away, repress, or in any way become blind to it), and then turns in increased longing towards God, in whom lies our own Good which sin misses the mark of. Note that without the apprehension of sin, we cannot have repentance, and there is no grounds for an increased longing for communion with the divine. But simultaneously, without this turn towards God, the apprehension of sin does not 'lead to salvation without regret,' but only unto grief and death.